THE ART OF FASHION PHOTOGRAPHY

Here are some images from my archive of favorite photography.

One Hundred Years of Fashion Photography

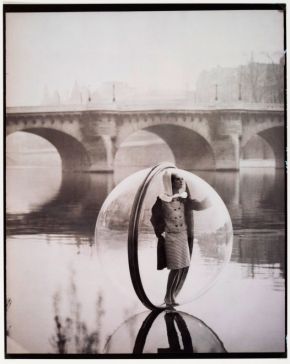

Melvin Sokolsky, Simone wears fashion by Venet, River Seine, Paris, American Harper’s Bazaar, March 1963, © Melvin Sokolsky/Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The photographer David Bailey described a fashion photograph simply as ‘a portrait of someone wearing a dress’. The roots of the profession are found in Victorian society portraiture. From as early as the 1840s, debutantes, actresses and dancers posed in their finery for portrait photographers, just as their mothers had sat for the great portrait painters of their day.

Yet Bailey’s own work shows the transformative power of the camera lens. Irving Penn, the photographer with the longest tenure in the history of Vogue magazine, saw his role as ‘selling dreams, not clothes.’ Beyond the simple recording of fabric and surface detail, the most memorable images fulfil or challenge the desires and aspirations of the viewer.

Fashion photography has never existed in a vacuum. Photographers have continually pushed boundaries, and the tension between artistic and commercial demands has generated great creativity and technical innovation. Whether as fashion shoots or advertisements, these images reflect contemporary culture, world events and the dramatic shifts in women’s roles throughout the 20th century.

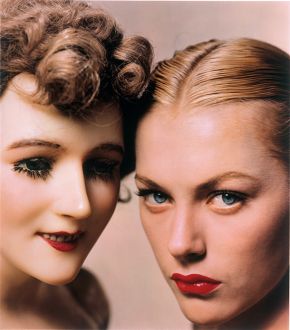

Cecil Beaton, In the Manner of the Edwardians, Mary Taylor wears Channel, American Vogue, 1935. Museum no. PH.191-1977, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A glittering new century

In 1911, at the height of Europe’s golden age of prosperity and elegance, the American photographer Edward Steichen photographed models wearing dresses by the designer Paul Poiret. Thirteen soft-focus images were printed in the magazine Art et Décoration, and Steichen later proclaimed them ‘the first serious fashion photographs ever made.’

In an earlier, pre-photography age, fashion magazines such as Le Costume Français and Journal des Dames et des Modes had included engraved illustrations but had only a limited readership. Advancements in printing processes in the 1890s allowed photographs to be printed on the same page as text, and fashion magazines became more widely available.

In 1909, the publisher Condé Nast bought an American social magazine entitled Vogue. He transformed it into a high-class fashion publication with international aspirations. Swiftly followed by the re-launched Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue sought to capture the spirit and fashions of New York, London and Paris through innovative photography and a growing supply of glamorous models.

Ilse Bing, Salut de Schiaparelli, Perfume Advertisement, 1934, © Estate of Ilse Bing/Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Challenging perceptions

The cultural movement of Surrealism had a profound impact on fashion magazines in the 1920s and ’30s. Paintings by Salvador Dalí and Giorgio de Chirico featured in Vogue alongside avant-garde photographs by Man Ray. Some fashion photographers adopted their revolutionary principles, attempting to give visual expression to the unconscious mind. New techniques and unexpected juxtapositions were used to challenge perceptions of reality, to amuse and to disturb.

Such bold experiments riled Vogue editor Edna Woolman Chase, who wrote angrily to her staff in 1938:

‘Concentrate completely on showing the dress, light it for this purpose and if that can’t be done with art then art be damned. Show the dress.’

As chief photographer of French Vogue, and later of Harper’s Bazaar, Baron George Hoyningen-Huene inspired a generation. His own work reflected a painterly fascination with light, shade and classical forms. His protégé Horst P. Horst produced similarly inventive images, fusing surreal and classical motifs.

Erwin Blumenfeld, Model and Mannequin, American Vogue Cover, 1 November 1945, © Estate of Erwin Blumenfeld/Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Post-war revival

During the Second World War ‘make do and mend’ was the prevailing approach to fashion. As the world gradually recovered from the horrors of war, a fresh cohort of designers emerged. The desire to embrace glamour and femininity after years of wartime austerity found its most extreme expression in Christian Dior’s New Look, launched in 1947, with its nipped-in waists and extravagantly full skirts.

The elegantly sensual vision of photographer Lillian Bassman complemented the new fashions. She pioneered an approach in which evoking a mood took precedence over depicting the details of the clothes. Bassman’s grainy images frustrated Harper’s Bazaar editor Carmel Snow, who warned her in 1949,

‘You are not here to make art, you are here to show the buttons and bows.’

Erwin Blumenfeld also pushed the boundaries of experimental fashion photography. He favoured Kodachrome colour film, which enabled his vivid images to leap from the magazine page.

John French, Skater wears a Digby Morton fur trimmed velvet coat, city gentleman, Michael Bentley in the background, London. Daily Express, 1955, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Shooting in the city

In the 1950s a fresh dynamism infected the major fashion magazines as photographers adopted a more spontaneous, photojournalistic approach. Models spilled out onto city streets, studio backdrops were replaced by city skylines.

In 1957 Richard Avedon photographed a model striding along the Place François-Premier in Paris for American Harper’s Bazaar. She appears mid-step, her Cardin coat billowing behind her. Both feet are off the ground, as though a gust of wind has lifted her into the air. Avedon titled the photograph In Homage to Munkácsi, a reference to one of the first fashion photographers to work primarily outside the studio. Writing ahead of the trend in his 1935 article Think While You Shoot, Martin Munkácsi advised:

‘Never pose your subjects. Let them move about naturally. All great photographs today are snapshots.’

This new cinematic vision was vigorously promoted by the powerful art directors Alexey Brodovitch at Harper’s Bazaar and Alexander Liberman at Vogue.

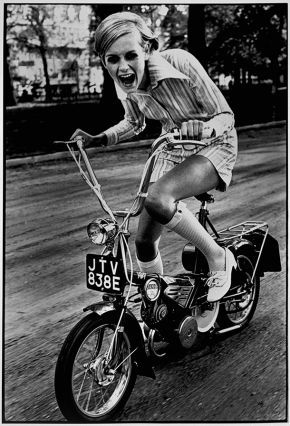

Ronald Traeger, Twiggy wears Twiggy Dresses, Battersea Park, London. Unpublished Fashion Study for British Vogue, Young Idea, July 1967, © Estate of Ronald Traeger/Vogue The Condé Nast Publications Ltd/Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Sixties liberation

In the 1960s the feminist movement gathered pace as women campaigned against inequality. In the fashion world, the structured formality of 1950s designs gave way to a more youthful look and the body was liberated from constricting undergarments and corsetry. New designers and photographers emerged, their work showcased in magazines such as Queen (relaunched 1957) and Nova (launched 1965).

Photographer David Bailey was employed to revamp the ‘Young Idea’ section of British Vogue. His vivacious documentary approach, and those of other London-based photographers, turned teenage models such as Jean Shrimpton and Twiggy into international stars, the embodiment of Swinging London. The mood was captured in Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blowup (1966), in which David Hemmings starred as a character partly based on Bailey.

From 1966 onwards, exotic fabrics, clashing patterns and colours were boldly combined. Penelope Tree’s unconventional looks made her the ideal model for the hippy fashions popular in the latter part of the decade.

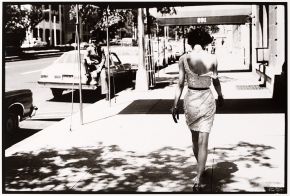

Arthur Elgort, Wendy Whitelaw, Park Avenue. Personal picture taken on American Vogue fashion shoot, July 1981, © Arthur Elgort/Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Picturing femininity

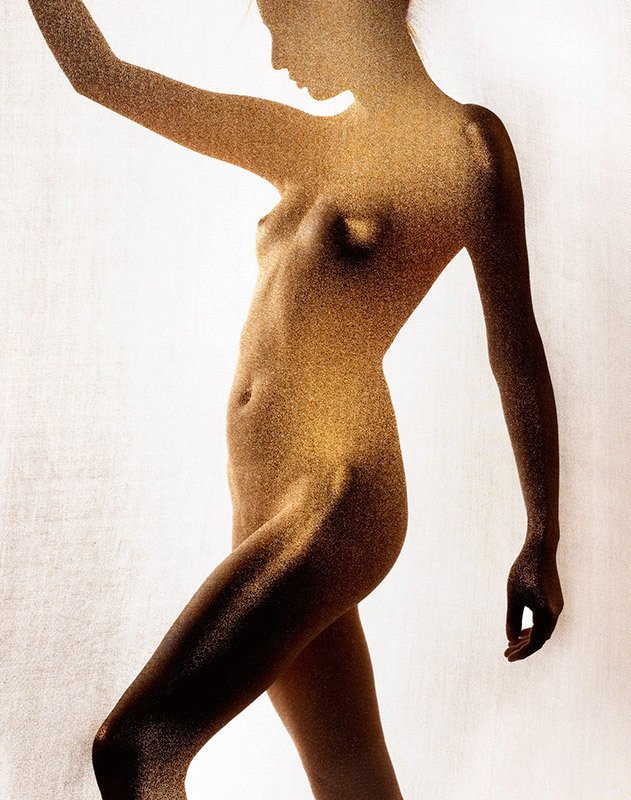

In the 1970s photographers increasingly tested the limits of acceptable fashion imagery. They engaged with society’s changing attitudes towards femininity and sexuality, and the potentially controversial themes of religion and violence often informed their work.

These fashion images invited viewers to be voyeurs of highly charged scenes. Helmut Newton’s work brought together themes of emotional ambiguity and sex, capturing confident women in glamorous and contrived settings. Guy Bourdin and Gian Paolo Barbieri created darkly provocative images, which focused less on garments and more on the character of the woman beneath.

The notion of ideal beauty broadened in mainstream magazines with the more regular use of black and androgynous models. The photographers Deborah Turbeville and Sarah Moon were both former models and their engagement with the female form was distinct from that of their male counterparts. Their contemplative images provided female perspectives on the themes of beauty and sexual objectification.

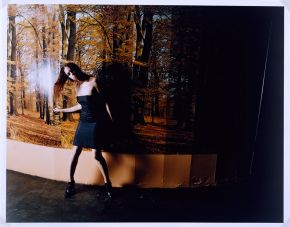

Corinne Day, Woman dancing at a London club, 1992, © The Estate of Corinne Day/Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Capturing real life

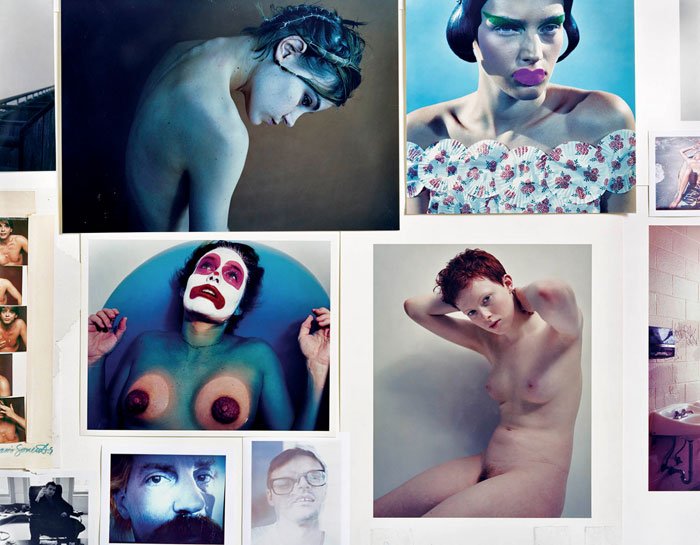

In the 1980s, new style publications aimed at both sexes emerged as a counterpoint to the airbrushed perfection of the major glossy magazines. They featured articles on contemporary music, culture and emerging trends. Their pages were populated with figures representing alternative types of beauty, who were often not professional models.

Portraits by Steve Johnson of punks and New Wave youth appeared in i-D magazine. The images became known as ‘straight ups’ as they showed the figure in full. The approach garnered many imitators, keen to capture personal and innovative street fashions.

In the 1990s, the leading exponents of this naturalistic, documentary approach to fashion photography included Corinne Day, David Sims, Craig McDean and Jason Evans. At the heart of their work lay an interest in everyday life and real people, celebrated for all the flaws that make them individual and uniquely beautiful.

Fiction and fantasy

Today’s most dazzling fashion images are rich with colourful and poetic narratives. Big budgets, set designers and multiple stylists are employed to create elaborate fantasies. Photographer Miles Aldridge describes the process as akin to making a film:

‘If the world were pretty enough, I’d shoot on location all the time. But the world is just not being designed with aesthetics as a priority. What I’m trying to do is take something from real life and reconstruct it in a cinematic way … condensed emotion, condensed colour, condensed light.’

Just as fashion designers reinvent and recycle the trends of decades past, photographers often look to their forebears for inspiration. Tim Walker conjures a whimsical, technicolour England, inspired by the opulence of Cecil Beaton’s early work and classic children’s fairytales.

For the past century women’s fashions have dominated magazines, but in recent years more publications aimed at male readers have emerged. The V&A is now consciously collecting men’s fashion images to reflect this growing area.

This content was originally written to accompany the display Selling Dreams: One Hundred Years of Fashion Photography, on at the V&A South Kensington 28 March – 4 May 2014

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.